Introduction

“My daughter stopped talking to me the day she discovered the nature of my job.”

This heartbroken statement is from a manual scavenger, which reflects not only a father’s pain but also highlights the widespread shame, humiliation, and unseen suffering faced by infinite individuals caught in this inhumane practice of manual scavenging. Manual scavenging involves manual removal and disposal of human excreta from insanitary latrines, is not only job but it is more deeply connected to caste discrimination, poverty, and social exclusion and Manual Scavenging in India is a scary problem.

In India, for generations, some communities have been forced into this degrading work because of their caste. Though the Indian Constitution tried to end these practices by the abolition of untouchability and the prohibition of its practice in any form under Article 17, promising the right to live with dignity under Article 21 by protecting life and personal liberty. however, the daily lives of manual scavengers show that there is still a big gap between these ideals and reality.

Alarming Data

According to the Government of India, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No. 2695, 18 December 2024), there have been no deaths due to manual scavenging. However, 419 sanitation workers have died in the last five years while cleaning sewers and septic tanks. As per the report of national commission for Safai Karamchari there were 954 people died because of this dangerous sewer work from 1993 to 2021.

After reading this, the question arises that why even after rules and regulations people are dying? So, the answer is within the ambit of this work itself that people are no more wanting to do this but their caste, social stigma, and our society forced them to do so. How shameful it is to be the part of that type of society which want cleanliness but don’t want to do so, but still good to assign others.

Legislative Framework in India

THE PROTECTION OF CIVIL RIGHTS ACT, 1955

Basically, this Act implemented article 17 of Indian constitution to declare the untouchability as an offence. manual scavengers considered untouchables in society and suffer from discrimination and hence this discrimination with manual scavengers is considered as an offence in this act.

THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989

This act makes this illegal to hire someone from Schedule Caste or Schedule Tribe to do manual scavenging. The act was passed to punish the atrocities against Schedule Caste & Schedule Tribe.

THE EMPLOYMENT OF MANUAL SCAVENGERS AND CONSTRUCTION OF DRY LATRINES (PROHIBITION) ACT, 1993

It was the first major step taken by the parliament to directly address the issue of manual scavenging in India. This act prohibits the employment of manual scavengers and construction of dry latrines, however the act also had many loopholes;

- The definition of manual scavenger was not clear.

- Act did not provide any rehabilitation provision.

- There were no alternative means of livelihood to manual scavengers. provided

- Act also failed to emphasize the caste-based discrimination which is the main cause of manual scavenging in India.

- Lack of implementation, insufficient funds and no accountability led the continuity of this inhumane practise. This act undermined the rights and dignity of worker. And the new law came into force later.

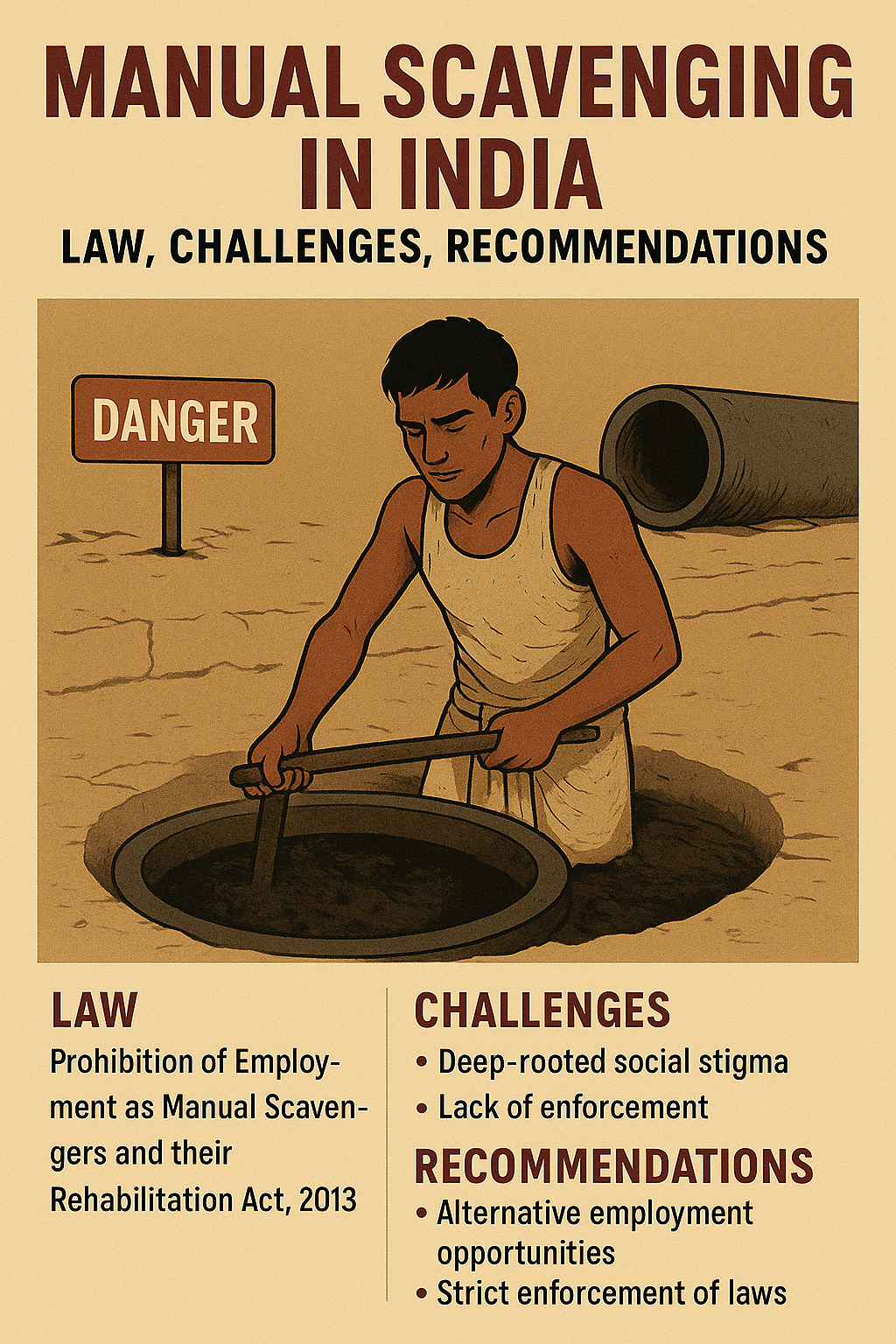

THE PROHIBITION OF EMPLOYMENT AS MANUAL SCAVENGERS AND THEIR REHABILITATION ACT, 2013

First and foremost, the act provides the solution of alternative means of livelihood, and established the provision of rehabilitation, of workers and their family members, it emphasized the dignity of worker and recognised manual scavenging as a violation of human right, which was absent in previous act of 1993. Here are some important provisions of this Act;

- The act prohibits the employment of manual scavenging.

- Act bans the construction and maintenance of insanitary latrines.

- Act provided the provision of penalties in contravention of this act.

- Act decentralized the implementation and accountability by inclusion of various authority, municipal corporation, railways and cantonment boards.

- This act also provided multiple vocational training programme, financial assistance, concessional loans scholarships for student who belong to manual scavengers’ family.

However still there is ineffective enforcement of regulation, bureaucratic delays and lack of awareness among the society, which hinder the implementation of these progressive laws that exist only on paper.

Judicial Rulings

Safai Karamchari Andolan & Ors vs Union of India & Ors on 27 March, 2014

In this case Supreme Court given guidelines aiming to abolish the manual scavenging in India;

Fundamental rights– Manual Scavenging is a violation of Articles 14, 17, 21, and 23 of Indian Constitution, which are Equality before law, Abolition of Untouchability, Protection of life and personal liberty and Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour, respectively.

Casteism– Court considered state sanctioned casteism as a violation of human dignity.

Definition– the term “sewer” as per Sec. 2(q) of the 2013 Act now also included stormwater drains cleaning workers.

Accountability– FIR should be filed not only against contractors but also against leader of local bodies.

Compensation revised– 30 lakhs from 10 lakhs in case of death, 20 lakhs for permanent disability, 10 lakhs for injury. Jobs opportunities and group IV post in government job should be provided to family members.

Mechanisation– All cleaning of sewers, septic tanks, and storm drains must be done by using machines. No individual should have to enter sewers or septic tanks.

Apart from this, free health check-ups should be provided for sanitation workers. Scholarships and educational opportunities for the children of scavenger families should be offered. Campaigns should be run to raise awareness to eliminate this social stigma in society.

Dr Balram Singh vs Union of India on 20 October, 2023

SC ruled that manual scavenging is a violation of articles 17, 21 and 23 of the Indian constitution. In this case Justice S Ravindra Bhat instructed to the union and states to completely automate and mechanise cleaning of septic tanks and sewer to eradicate all forms of manual scavenging in India. The Court also mandated skill training, alternative livelihood opportunity, and ₹30 lakh compensation for sewer deaths, and rehabilitation for those who have been impacted.

Delhi Jal Board vs National Campaign Etc. & Ors on 12 July, 2011

In this case the Court rules that sewer workers must be given safety gear and protection; if workers die while working, their family must get fair compensation. Court emphasised on the role of courts and government, that, government agencies cannot escape the responsibility, and courts have a duty to protect the right and dignity of the poor. Court also enhanced the compensation.

Challenges in Manual Scavenging

Legal Gaps

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, does not define manual scavenger, this limited scope left many sanitation workers without legal safeguards. Although the law mentions “protective gear”, it fails to define these.

Enforcement Failures and Low Conviction Rates –

Despite the fact that manual scavenging is banned, rates of conviction are still very low. Deaths resulting from the cleaning of sewers or septic tanks are frequently being misclassified under Section 106 of BNS (negligence) instead of being prosecuted under the Manual Scavenging Act, Reports shows that there have been no convictions under the Manual Scavenging Act so far.

Hidden Data

The true number of manual scavengers underreported by official government data. higher figures are provided by organisations like Safai Karamchari Andolan, which suggests a pattern of underreporting and concealment of facts and data.

Caste Stigma

The majority of manual scavenging is performed by Dalit sub-castes, including Valmiki, Hela, and Lalbegi and identified by Bhangi. Approximately 95% women involved in rural areas in the work of toilet sanitation are from these communities. This Social stigma, the practice of untouchability confines these groups to this demeaning work with minimal opportunities for their advancement.

Lack of Rehabilitation Mechanisms

Rehabilitation has not worked well because beneficiaries are not identified properly, money also reaches them late, no proper skill training programmes are monitoring. As a result, most former manual scavengers are still in poverty and face social stigma, which hinder the main purpose of rehabilitation.

Technological Gaps in Sanitation Systems

While home appliances have improved a lot, sanitation technology is still backward. Workers still use old machines and unsafe methods, and there is less mechanisation in reality. Even when money is given for better machines, it is not used properly on the ground.

Gendered Vulnerability

Over 90% of manual scavengers are women, who suffer not only dangerous working conditions but also face wage discrimination and sexual harassment. The lack of gender-sensitive rehabilitation policies help to intensify their vulnerabilities.

Delegation of Responsibility

Local governments are still hiring private contractors for cleaning services, and then refuses to accept liability in the event of fatalities, resulting families get no compensation.

Health Risks & Human Rights Concerns

Employees have to face harmful gases such as methane and carbon monoxide, resulting in long-term health issues and a high incidence of fatalities. The absence of protective equipment and health insurance violates Articles 14, 21, and 47 of the Constitution.

Government Schemes and Initiatives for Eradication of Manual Scavenging

Self-Employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers (SRMS / SESRMS)

The scheme provides a one-time financial grant of ₹40,000 to each family, a capital subsidy of up to ₹5 lakh for alternative livelihood opportunities, skill development programmes accompanied by a monthly stipend of ₹3,000, and health insurance coverage under the Ayushman Bharat–PMJAY scheme.

National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE), 2023

The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment implemented this scheme to stop all deaths in sanitation work. It ensures only trained workers with machines handle waste. The scheme also supports self-help groups, gives loan to sanitation businesses, and provides health insurance under Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana.

Swachhta Udyami Yojana (NSKFDC)

The program offers affordable loans to sanitation workers, manual scavengers, and Urban local bodies to enabling them to access sanitation vehicles and equipment. The goal is to promote more mechanisation in cleaning processes.

Swachh Bharat Mission & SBM-Urban 2.0

This flagship national sanitation initiative emphasises on eradication of unsanitary latrines and the deployment of mechanised cleaning alternatives. Under SBM-U 2.0, a sum of ₹371 crore has been allocated to states specifically for the purchasing sewer cleaning machinery in smaller urban areas.

National Safai Karamcharis Finance and Development Corporation (NSKFDC), 1997

The apex financial organisation for Safai Karamcharis gives low-interest loans to help sanitation workers to start small businesses and earn. It especially supports women and people with disabilities to become self-reliant.

National Scheme of Liberation and Rehabilitation of Scavengers (NSLRS), 1992

The programme gave training, stipends, tool-kits, and up to ₹50,000 as financial help. It also encouraged people to work together in groups to change dry latrines into proper sanitary toilets on a large scale.

Integrated Low-Cost Sanitation (ILCS), 1981

By eliminating manual waste management methods, the programme focuses on converting dry latrines into sanitary twin-pit latrines, and it is linked to scavenger rehabilitation.

Total Sanitation Campaign (1999) → Swachh Bharat Mission 2014

This rural sanitation initiative it aims to reduce reliance on manual cleaning techniques, eradicate open defecation, and achieve universal access to sanitation facilities.

Nirmal Gram Puraskar, 2003

This programme gave rewards to Gram Panchayats, Blocks, and Districts for becoming Open Defecation Free (ODF), and making rural sanitation efforts more effective and attracting.

Pre-Matric Scholarship Scheme (Children of parents in Unclean Occupations)

In this scheme the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment offers scholarships and financial assistance to students from Classes I to X, whose parents are involved in hazardous occupations such as manual scavenging, tanning, and flaying. The objective is to reducing dropout rates and remove the societal stigma associated with these professions.

Pay-and-Use Toilet Scheme

This urban initiative aimed for establishing community toilets in slums and densely populated areas. It effectively diminishes the use of dry latrines and improves sanitation for poor people living in cities

National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (1994–ongoing)

This is a statutory organisation monitoring the execution of welfare initiatives, addresses grievances and engaged in policy advocacy for sanitation workers and manual scavengers.

Key Recommendations

Legal Reforms & Accountability –

By broadening the scope of manual scavenging definitions in the Act of 2013 to include all contemporary sanitation activities. Additionally, by imposing strict liability on contractors and municipal authorities for fatalities occurring during cleaning tasks.

Reliable Data Collection –

It’s very important to have trustworthy sources to get information. National polls, surveys by local district offices, and simple technologies like online apps and toll-free helplines can all be used to do this.

Rehabilitation and livelihood Support –

Rehabilitation and livelihood support can be better by raising wages and tying programs like MNREGA to rehabilitation, as well as making sure that vocational training programs are carried out properly. The provisions for housing, financial loans, pensions, social security benefits, and access to quality education are crucial to promote the better livelihood of manual scavengers and their family.

Technological and Infrastructural Reforms –

Sewer and septic tank cleaning should be fully mechanised using advanced equipment. Regulations should support decentralised waste management systems to reduce human contact with harmful waste.

Social empowerment and awareness –

To empower the society and to raise awareness, campaigns should be run across the country to discourage caste-based discrimination. The government must make sure that policies like reservations and fair job opportunities, are properly implemented. People should also understand that sanitation work is important and respectable, and sanitation workers deserve dignity and respect.

Conclusion

In the 21st-century, the presence of manual scavenging in India not only shows a failure of policy but also representing a deep moral crisis and violating the foundational principles of democracy. Every year, hundreds of workers mostly women from Dalit communities are forced to do this dangerous and degrading work, and many of them die from asphyxiation in unsafe sewers.

Such practices constitute a significant obstacle to India’s fulfilment toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Also, the improper disposal of human waste also leads to environmental degradation and hence is represents both ecological harm and social injustice.

Movements such as Rastriya Garima Abhiyan, Safai Karamchari Andolan, and Their Voice have been fighting to end the manual scavenging for decades, but the struggle continues. Ending caste discrimination and this inhumane practice is not just about the government’s job It’s our duty too. We should question caste-based practices in our daily lives and push for machines to do dangerous cleaning and never accept manual scavenging as “normal”.

Eliminating manual scavenging is a fundamental reaffirmation of the constitutional ideals of justice, dignity, and equality. Ending manual scavenging is not only about better sanitation, but it is also about protecting human rights and human life.

About Author

Varsha, a final-year law student at the Department of Legal Studies and Research, Barkatullah Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal, learner and aspirant in the field of law, Curious by nature, she likes to explore everyday obvious moral and social issues that often have deeper meanings. Her goal is to integrate law in daily real world applications.